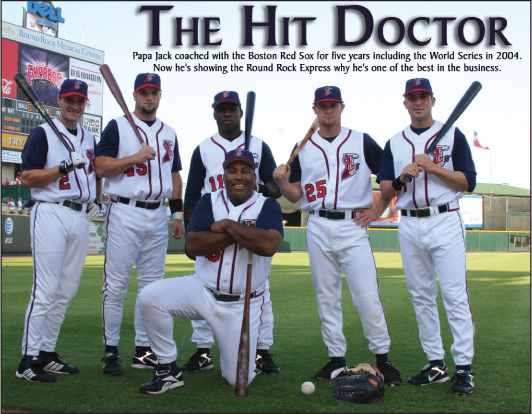

The year was 1971.

The year was 1971.

As a high school senior, Ron Jackson had options; lots of options. In football, the likes of Tennessee, Stanford, and USC came calling with the hopes the running back-linebacker would choose their school. So too did a certain home state school and its legendary coach known for his national championships and houndstooth fedora. Yes, even Bear Bryant and Bama wanted the services of Jackson. When decision time ultimately came, Jackson spurned all those schools, not to mention the sport. Instead, he signed a contract with the California Angels, who selected him as the second pick overall behind pitcher Frank Tanana.

After being drafted, Jackson spent four years toiling in the minor leagues. Then, in 1975, he finally got the call. He was going to the big leagues.

Once he arrived in California Jackson found himself hanging out with a veteran pitcher who had an affinity for lots of stretching both before and after practice. In short time the pitcher took Jackson under his wing and they developed a friendship. The pitcher was none other than Nolan Ryan.

Jackson said Ryan always offered him advice including one suggestion that Jackson might be better served as a catcher in the Major Leagues. It never happened. While Ryan failed to convert Jackson to a potential battery mate, he succeeded in doing something that has left a lasting impression on Jackson and those who have met him.

“I was always called ‘pop’ because I looked like my dad. Whenever our first child was born, Nolan said I’m going to call you ‘Papa Jack.’ A lot of people (today) don’t know Ron Jackson. They know Papa Jack.”

Papa Jack bounced around the Major Leagues from 1975-1984 with the Angels, the Minnesota Twins, the Detroit Tigers, and the Baltimore Orioles. In 1985 Jackson moved from the field to the front office of the organization where it all started. For several months Jackson worked in the Angels public relations department. It wasn’t where he wanted to be.

“I wanted to get down on the field. I feel like God gave me talent for helping people when it comes to baseball and hitting,” Jackson said.

In 1988 Jackson got his wish when the White Sox organization asked him to serve as the hitting coach and first base coach with Triple-A Vancouver.

“Larry Hines was the GM for the White Sox. He was at one time the scouting director for the Angels. He knew me already. The biggest thing he was looking for was getting good people—someone who would work with the kids and would be there for them. Working with Triple-A is not easy. You have to have a good personality and know how to work with people.”

Jackson had both. Seven years later including a couple positions in the Brewers organization, he returned to the White Sox, this time as the parent club’s first base coach. After a circuitous trip through the minors, this time as a coach, Jackson had finally made his way back to the big leagues. A couple years later the White Sox named Jackson the team’s hitting coach.

Over the course of the next few seasons Jackson proved he was not only a good person, but also a good hitting instructor. Working with the likes of Frank Thomas and Robin Ventura, the White Sox hitters improved in all categories up and down the lineup.

How did it happen so quickly? What was Jackson’s secret?

According to Jackson, it’s not one specific thing. There are a variety of factors when it comes to hitting.

From the technical standpoint, where the Charlie Laus and Walt Hriniaks have made names for themselves in the world of baseball, there are basic fundamentals to a swing. Jackson said it all comes down to the front foot. What happens before the front foot is planted doesn’t really matter. That’s why he said you see so many hitters in awkward positions—hands low or high—before their lead foot hits the ground. Whenever the foot is planted, that’s when everything must come together.

“It’s like a building. You have to have a foundation and you start from the feet and work your way up. You build it with concrete, not sand. Once the feet are on the ground, you better be ready to fire.”

Jackson said if you watch closely, you will see the good hitters are in a good position at that point in their swing. Bad hitters are not. Something else that separates good hitters from bad—the plan they have when they come up to the plate.

“Good hitters are always getting ahead in the count. Bad hitters always seem to get two strikes on them and swing at bad pitches. They don’t have a plan.”

While Jackson has produced successful hitters wherever he has been, he said it goes beyond mechanics, beyond a basic hitting plan.

“The players at this level know the mechanics part of it. But I can see things other people can’t see. I can watch them two or three swings and see what’s wrong right off the bat. Teaching and coaching is learning how to get it through to each player. It’s not being a robot. You have to be a mother, a father, an uncle for these players. That’s my approach so you can get everything out of them. You can’t treat them the same way. You have to learn how to deal with them. And you do that by spending time with your players—in the cage, playing soft toss. They get to know me and I get to know them.

“A lot of the hitters are doing the same thing. You’ve got to know what to look for, and once you see it and spot it, you have to correct it. A lot of the guys say, ‘I know I’m doing this. How do I fix it?’ That’s where I come in. That’s why it’s important to get to know your players. Once they know themselves they can talk to you and tell you. It’s like when you go to a doctor. When you go to the doctor, he asks how you’re feeling. You’ve got a cold or you’re coughing. He can go back and relate because someone else has got it and he writes a prescription and gives you what you need. Now you can go fix it.”

A perfect example of this occurred back in 2002, Jackson’s first season with the Red Sox. Actually, as a point of reference, you have to look at the 2001 season. That’s when the Red Sox hit for a .266 avg., which included hitting 316 doubles and 198 home runs. After Papa Jack, The Hit Doctor, arrived, the Red Sox hitting numbers improved dramatically. In 2002 the team batting average bumped up 11 points to .277 and they hit 348 doubles. There was a slight dip in home run production from the previous year dropping to 177. In 2003 the team more than made up for it with an incredible hitting season batting a collective .289 with 371 doubles and 238 home runs. Those first two seasons under Jackson the Sox led the Majors in runs, team batting, doubles, total bases, and on-base percentage. He had without question

made a huge impact with the hitters at Boston. The best was yet to come.

The 2004 season for the Red Sox can best be described as magical. Jackson once again was waving his wand as the hitting instructor. That season the Sox tied a Major League record with 373 doubles and led the Major Leagues with 238 home runs. They also set Major League records for extra-base hits, total bases and slugging, while falling just two doubles shy of the all-time mark. It almost went for naught in the playoffs when the Red Sox fell behind the hated New York Yankees 3-0 in the American League Championship Series.

The 2004 season for the Red Sox can best be described as magical. Jackson once again was waving his wand as the hitting instructor. That season the Sox tied a Major League record with 373 doubles and led the Major Leagues with 238 home runs. They also set Major League records for extra-base hits, total bases and slugging, while falling just two doubles shy of the all-time mark. It almost went for naught in the playoffs when the Red Sox fell behind the hated New York Yankees 3-0 in the American League Championship Series.

Jackson said while the situation looked bleak to Red Sox Nation and the millions watching on television, especially considering no team in baseball history had ever come back from a 3-0 deficit, those on the Red Sox bench believed. They knew they needed just one win to provide a spark.

“That last game where they beat us in Boston 19-8, they thought it was over. They were having a good time laughing and partying. We knew we had to win tomorrow. It’s do or die. We kept telling ourselves they better not let us win one game. All we got to do is win one game. Instead of closing the door on that one game, we won. We then had a great chance of winning.”

Still down 3-1, Jackson knew the ALCS was far from over, but in order to improve their chances, he needed to get his No. 1 and 2 hitters, Johnny Damon and Mark Bellhorn, going.

“When we got to New York (for Game 5), I knew I had to get them to the cage and get them straightened out. Ellis Burk was on the disabled list but he was a veteran that the players listened to. I told him to tell Damon and Bellhorn to get off their card playing (in the locker room) and get down to the cage and do some extra work. They were messing with my ring. I needed one too.”

Burk conveyed Jackson’s message. Both Damon and Bellhorn showed up at the cage and worked with Jackson. The results were dramatic. Bellhorn hit a three-run homer in Game 6 and followed it with a solo shot in Game 7. In Game 7 Damon was huge as he hit a grand slam and added a two-run homer. He finished the game with three hits after only three hits prior to that in the entire series.

“I knew exactly what they were doing. I take my hats off to them because they came down and they listened and tried. After they won, I’ll never forget, I had my little video camera going around talking to the guys asking how do you feel about beating the Yankees four straight. Damon said, ‘Thank you for dragging my butt down to the cage.’ Bellhorn said, ‘We wouldn’t have won it without you Papa Jack.’”

As they say, the rest is history.

Unfortunately for Jackson, just two years after reaching the pinnacle in Major League Baseball, he was history. The Red Sox let him go. It was a surprise to the Boston media, to the fans, and to the players. It wasn’t necessarily a surprise to Jackson himself.

“They were looking for an out because I was there before Terry Francona got there. Francona wanted to have his guy in there. I think he was waiting for the time to get me out of there,” Jackson said.

After the 2006 season was apparently the best time to do that as the Red Sox batting average dipped to .269 (still better than ’01, the season before Jackson arrived) and the home runs dropped to 192. According to Jackson, there was a good explanation for the lack of production at the plate.

“We lost the whole team in the second half of the season after the Yankees beat us four straight. All kinds of pitchers coming up and down. David Ortiz (heart problem), Jason Varitek (knee surgery), Trot Nixon (back problems and knee surgery) all were out of the lineup at some point.”

Despite a less-than healthy lineup, someone had to take the blame. It was Jackson. He was out of the Red Sox organization. The next question was—where would he land?

Enter Jackie Moore. The Round Rock skipper made an unsolicited call to Jackson this past offseason.

“He said he hadn’t been around me, but he had watched and seen my work ethic and would love to have me here in Round Rock. I had a chance to talk to Nolan and Don Baylor and they both said if you’re going to be anywhere in the minor leagues, Round Rock is the place to be. Other teams tried to call me including the White Sox and Rockies but I decided I would go back to the minor leagues and work my way back up again.”

In less than half a season with the Express, Jackson is very happy with his decision. Much like he has done before in his previous coaching stops, Jackson has tried to develop relationships and trust with the players.

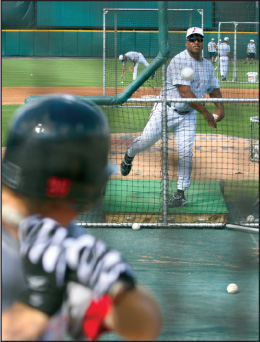

“All these guys are really open minded and wanting to learn. The first couple of weeks I didn’t say too much. I just watched and observed. Then we started to pick it up. We sat them down and gave them a plan what they need to do in certain situations. How to hit with two strikes. I had to make sure I had a maintenance program and work with these guys each day doing soft toss, tee work. A lot of people don’t see what we do before the game. I always believe in making sure the guys get the work in that will take them to the next level.”

If his past success is any indication, it’s more than likely a few Round Rock Express players will make their way to the next level, Houston, thanks in part to a hitting instructor who not only taught them, but who took the time to get to know them. And with a little luck, that same hitting instructor might get the call-up as well